Written By: Conor Clark, CFA

CREDIT RATINGS VS. CREDIT SCORES

Most readers are likely familiar with credit scores. Based on a person’s history of borrowing and making timely repayments (or not), a credit score is a measure of an individual’s credit worthiness. Credit scores determine who is able to receive a loan, the interest rate paid, and the borrowing limits. Credit ratings serve the same functions for companies and other types of organizations.

Whether it stems from applying for a mortgage, a credit card, or an apartment lease, most of us have some direct experience with credit scores. Credit ratings, though, while conceptually quite similar, are generally less familiar.

Credit ratings and credit scores are both evaluations of the credit-worthiness of a borrower. The key difference: credit scores apply only to individuals, whereas credit ratings are assigned to companies, countries, and other types of organizations.

CREDIT RATINGS

A credit rating measures a corporation or government’s probability of default. In other words, an entity’s credit rating is an estimate of its likelihood of failing to make good on its financial commitments. Credit ratings are typically represented in terms of letter grades ranging from AAA (safest) down to C (riskiest).

When a company wants to borrow money, one of the largest potential sources is the issuance of bonds. When a company sells bonds to investors, the investors are effectively lending money to the company. A company that plans to issue a bond will usually hire a credit rating agency to assess its financial health and provide a rating. By obtaining the credit rating, the company helps investors evaluate the risk involved in the loan. Most investors don’t have the time, willingness, or expertise to perform in-depth credit research on a company. And remember, while a credit rating is a valuable tool in the investment research process, it is imprudent to rely on credit ratings blindly.

CREDIT RATING AGENCIES

Credit ratings are assigned by credit rating agencies, specialized companies that research and analyze corporations, municipalities, and countries’ financial standing. In the United States (and to a lesser extent globally), the credit rating industry is dominated by the “Big Three”: Moody’s Investor Service, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch Ratings. All three were founded more than a century ago and, together, they control 95% of the global credit ratings industry. A bond that is not rated by at least one of the Big Three is unlikely to garner much attention from investors.

To find a credit rating, investors can search by the name of the company (or country or other organization) on a rating agency’s website (see links above). Reading the full analysis and rationale for the rating requires a paid subscription, but anyone can view the ratings free of charge.

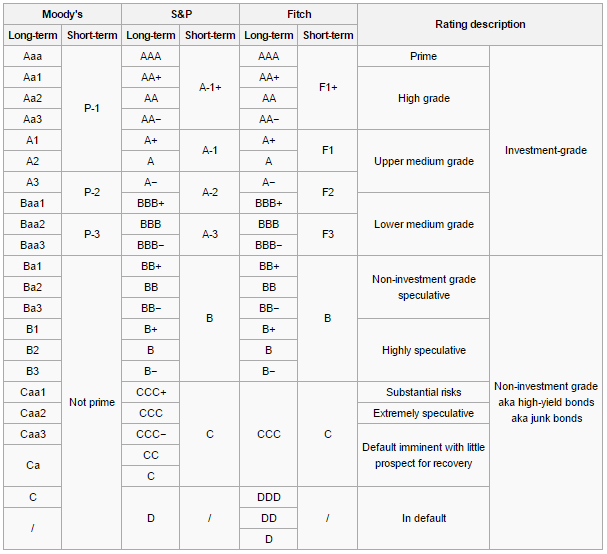

Each credit rating agency has its own ratings scale, but there are some clear parallels between them, as is apparent in the table below.

Source: Benzinga.com

As can be seen in the table, the biggest delineation is between “investment grade” bonds and non-investment grade “junk bonds.” Investment grade bonds are generally considered safe and secure, whereas junk bonds can involve considerable risk of default. From the perspective of a company issuing bonds, a downgrade from investment grade to junk has significant adverse consequences: The number of investors interested in their bonds will meaningfully shrink and the interest rate they will have to pay will increase.

PROBLEMS WITH THE CREDIT RATING SYSTEM

Though the credit rating system is reasonably effective, it definitely has some undeniable problems. These issues largely stem from the fact that the entire industry is dominated by just three credit rating agencies, all three of which share a business model that leads to questionable incentives.

Credit rating agencies are paid by the companies they rate. This arguably gives them the incentive to rate companies higher than they deserve in order to stay on the companies’ good side and ensure that the source of revenue continues—a clear conflict of interest. For example, prior to the financial crisis of 2008, many mortgage-backed bonds were rated AAA by the big three agencies and wound up worthless shortly thereafter.

So, while the opinions of credit rating agencies are definitely a useful resource, investors should use them as one component of a comprehensive analytical process and certainly shouldn’t trust them blindly.